In my Twitter (calling it “X” seems somehow wrong while also hilarious because that is subsequently the nonbinary/other gender marker on many state licenses) paroozing, I came across an account posting that psychology reimbursements were misogynistic based on proportions of providers of psychotherapy who are male or female.

Unsurprisingly, there are a ridiculously large proportion who are not male.

Now, I read this, thinking, Well, this is rage bait, and in that, there’s more data here than this account may be aware of how to look for.

So I found a page by Yardi (2024) mentioning the labor market breakdown of therapists, and something really caught my eye: About half of therapists who get reimbursed or paid have but only a Bachelor’s. This actually is why payment is low.

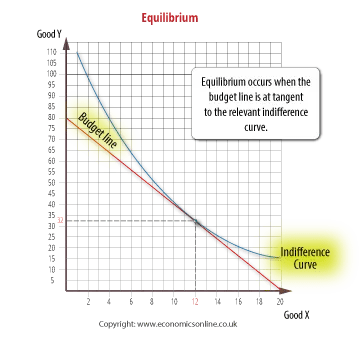

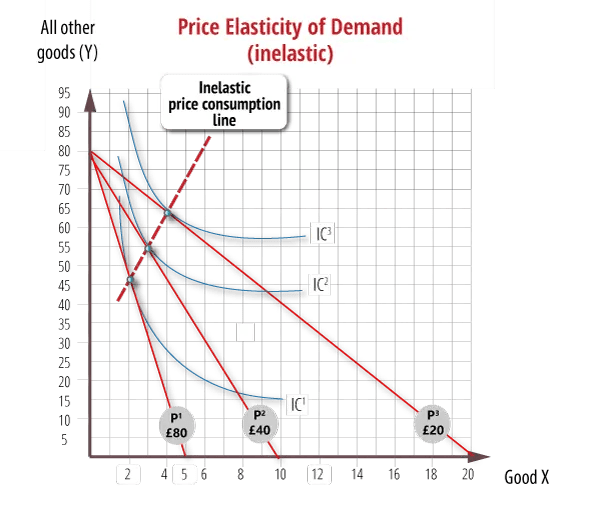

So below I placed two really intriguing graphs (Economics Online, 2020):

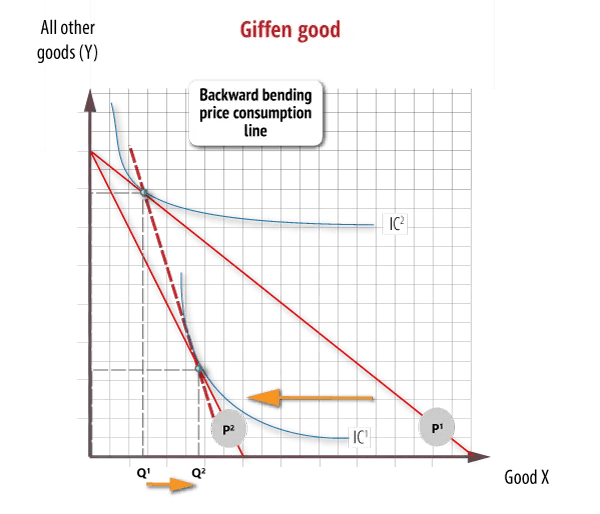

Economics Online (2020) has a third incredibly relevant graph. This one is a giffen good where we see that the indifference curve is super funky in comparison to a normal demand good, where it may be a market good (but is also not a public good, as those have yet a different indifference curve superimposed onto the quanity and price demanded).

So I’m sure a lot of you are going, “Well, that’s great and all, but I didn’t take fancy macro or micro economics coursework… ever… what on Earth do these mean?”

The graphs proivide guidance on how to read them, and I wanted to provide some insight as to how these are relevant. In the upper left quadrant, we have general indifference elasticity, where it’s elastic, not perfectly, but assumes normal demand and supply. This would be for goods we call “market basket,” where your quantity is pretty fixed and based on price you may be willing to purchase a substitute (a whole separate conversation).

Insurance reimbursement assumes we have not simply inelastic demand, like in the upper right quadrant, but also that, despite therapuetic services being economically classified as a Giffen good with inelastic demand, the average consumer has enough disposable income for them to assume elastic demand of the good.

This is a fancy way of saying, insurance models reimbursement based on projected amount of service visits needed to cure/solve/remediate the diagnosis. What elasticity tells us is how likely price is to impact quantity consumed. Elastic means that a change in price impacts the change in amount greatly, meaning that theoretically, our perceived value of the good is indifferent. Yet, with a Giffen good, we first assume that the consumer is purchasing the good independent of price. It sometimes is likened to a fancy phone or sports car, but technically, anything we consume that we care less about the monetary value and more about perceived value, is Giffen.

This is where healthcare insurance is weird.

Firstly, they use actuarial metrics to determine payment. So, basically, they go, “How likely is the provider to not do the job properly,” and through a lot of really fancy math and stats, poportion out the consumer’s responsibility of risk and theirs.

Secondly, this means that when some states provide reimbursement for varying and expanded levels of educated therapists, insurance has to spread risk evenly. They don’t really care if you personally as a provider are less likely to get malpractice claims, they more care if you’re in an area where more providers are less skilled/trained/qualified.

Thirdly, while we can argue all day about classism and structural social ineffiencies of assuming lesser educated providers are less competent, many times, they are not billing under their own license. There’s something called double ideminty which if you look it up sounds drastic. But all it technically says, in practice, is that because the non-independent provider’s claim goes through at least twice the amount of review, before and during submission, it is at least twice as risky.

And I for one am not going to pretend that the first patient I had got high quality care. I am not even going to claim I knew really what I was doing the first few months of diagnosing and assessing patients. There’s a learning curve that actuarially, is super expensive to insurers. The chance that my first few weeks of diagnostics needed to be re-done and double-billed are pretty solid.

Training clinicians is expensive for everyone.

The reason many psychotherapists get reimbursed proportionally less than they may be worth to their patient or community is because insurance has to model risk over actual market conditions. And they generally are risk-averse, meaning that they’ll do what presents them the least likely chance to have a lawsuit or third-party interference.

So yes, many therapists are female identifying or biologically female, but that’s not even close to where the problem resides. And as much as I want to say otherwise, the sheer fact exists that many schools exist to train therapists without many safeguards to ensure the therapist is accurately qualified or competent for their chosen area of practice.

Chances are that there are a lot of undergraduate degree therapists who mostly don’t pursue further training or education (CEUs are not comparable, and certifications are a different means of barrier to entry for many providers). This means that because the undergraduate degree coursework communicates foundational knowledge and one or two advanced areas, on average, at best, there’s no reason an insurer wouldn’t assume the provider, who is assumed a trainee, is simply acquiring learning experience.

Market prices when set by someone outside of the domain can look funny.

But honestly, when you read 10-K statements of fiduciary and insurance companies, there’s a lot of hope that they are helping, because the 10-K statements of therapuetic conglomerates look like someone tried to play Monopoly and made statements. The data is weird and most people analyze it with little conceptualization of clinical training processes and dynamics.

I wish my reader of this the best chances at feeling better about economies being confusing at best and completely off the rails at worst.

Warmly,

Dorthy B.

References

Economics Online. (2020). Indifference curves – prices and demand. Critics Capital, LLC. https://www.economicsonline.co.uk/competitive_markets/applications-of-indifference-curves-price-and-ped.html/

Yardi, S. (2024). Therapist Statistics 2024 By Therapy, Ethnicity, Sectors. Market.us Media. https://media.market.us/therapist-statistics/